Endomyocardial Fibrosis

Endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF) is a rare but serious form of restrictive cardiomyopathy that primarily affects the endocardium and the innermost layer of the myocardium. It is characterised by progressive fibrosis—an excessive deposition of connective tissue—in one or both ventricles of the heart. This leads to a stiffening of the ventricular walls, impaired ventricular filling during diastole, and eventually congestive heart failure. Endomyocardial fibrosis predominantly occurs in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and South America. Most commonly, it affects children and young adults, often resulting in chronic cardiac morbidity. While uncommon in developed countries, EMF continues to impose a considerable public health burden in endemic areas due to limitations in diagnostic infrastructure, low awareness, and insufficient access to therapeutic interventions.

|

| Image source Google |

Causes & Risk Factors

Although the definitive cause of endomyocardial fibrosis remains elusive, various environmental, infectious, and immunological factors have been implicated in its pathogenesis. Parasitic infections—particularly those involving helminths such as filarial worms and schistosomes—have been associated with hypereosinophilic syndromes, which are considered central to EMF development. Eosinophils, upon activation, release cytotoxic granules that incite inflammation and tissue damage, ultimately progressing to fibrosis. Nutritional deficiencies, especially of protein and micronutrients, have also been linked to EMF in low-resource settings. Genetic predisposition, autoimmune mechanisms, and chronic exposure to allergens are additional factors contributing to susceptibility. Social determinants such as poverty, poor sanitation, and limited access to healthcare exacerbate the risk, making EMF not only a medical but also a socioeconomic concern.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of endomyocardial fibrosis unfolds through three interrelated stages. Initially, an acute inflammatory response, typically mediated by eosinophilic infiltration, damages the endocardial lining. This inflammation can be driven by parasitic antigens or autoimmunity. The second phase is thrombotic, where the inflamed endocardium serves as a nidus for thrombus formation, increasing the risk of embolic events. The final and most chronic phase is marked by progressive fibrosis, characterised by collagen deposition, endocardial thickening, and calcification. This pathophysiological sequence leads to obliteration of the ventricular apex and subvalvular regions, impairing diastolic filling and reducing stroke volume. As fibrosis becomes more extensive, the heart’s compliance decreases, resulting in a rigid, underperforming myocardium.

Symptoms & Signs

Patients with endomyocardial fibrosis often present with symptoms reflective of chronic heart failure, including progressive exertional dyspnoea, fatigue, and peripheral oedema. Right-sided EMF typically causes hepatomegaly, ascites, and lower limb swelling, whereas left-sided involvement is more likely to produce pulmonary congestion, orthopnoea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea. Palpitations and chest discomfort are also common, with some patients experiencing atrial fibrillation due to atrial enlargement and endocardial scarring. In advanced cases, systemic embolisation resulting from mural thrombi may occur. On physical examination, clinicians may detect elevated jugular venous pressure, a third heart sound, murmurs indicating atrioventricular valve regurgitation, and signs of congestive hepatopathy. These clinical features underscore the importance of distinguishing EMF from other forms of cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing endomyocardial fibrosis requires an integrated approach combining clinical, imaging, and laboratory assessments:

-

Clinical History and Physical Examination – Initial evaluation should identify heart failure symptoms, risk exposures, and signs of right or left ventricular dysfunction.

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG) – May reveal low voltage QRS complexes, atrial enlargement, or arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.

-

Chest Radiography – Useful for assessing cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, and pleural effusions.

-

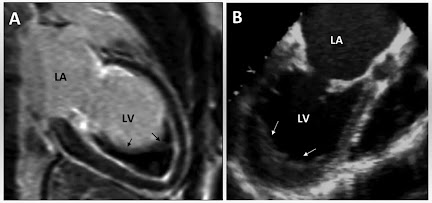

Transthoracic Echocardiography – Key diagnostic modality, revealing apical obliteration, endocardial thickening, and atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

-

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) – Offers superior spatial resolution to delineate fibrotic tissue and assess ventricular function.

-

Endomyocardial Biopsy – Although invasive, it provides definitive histopathological confirmation, demonstrating fibrosis, eosinophilic infiltrates, and myocardial degeneration.

-

Laboratory Investigations – Include eosinophil count, serologic testing for parasitic infections, autoimmune markers, and inflammatory biomarkers.

Treatment

Effective management of endomyocardial fibrosis necessitates a comprehensive and individualised therapeutic plan:

-

Allopathic Management:

-

Diuretics (e.g., Furosemide 20–80 mg/day) to relieve fluid overload and reduce symptoms.

-

ACE Inhibitors (e.g., Enalapril 5–10 mg/day) to reduce afterload and improve cardiac output.

-

Beta-blockers (e.g., Metoprolol 25–100 mg twice daily) for rate control and prevention of arrhythmias.

-

Oral Anticoagulants (e.g., Warfarin 5 mg/day with INR monitoring) to prevent thromboembolism.

-

Surgical Options: Endocardectomy and valve replacement may be beneficial in advanced or refractory cases.

-

Homeopathic Approach:

-

Crataegus oxyacantha (Mother tincture, 10–15 drops in water thrice daily) to enhance myocardial tone.

-

Digitalis purpurea (30C potency, twice daily) for improving myocardial contractility and controlling palpitations.

-

Treatment duration typically spans 3–6 months, with adjustments based on clinical response.

-

Ayurvedic Therapy:

-

Arjuna Churna (3–5 grams twice daily) as a cardiotonic.

-

Punarnava Mandoor (250 mg twice daily post meals) to address oedema and renal support.

-

Dashmool Kwath (15–30 ml twice daily) for its anti-inflammatory properties.

-

Ayurvedic therapy should be continued for 6–9 months under qualified supervision.

-

Unani Remedies:

-

Habb-e-Jadwar (1 tablet twice daily) to enhance cardiac function.

-

Sharbat Aijaz (10 ml twice daily) to support circulatory and respiratory health.

-

Duration typically ranges from 3 to 6 months, depending on patient response and clinical status.

Prevention

Preventing endomyocardial fibrosis hinges on addressing modifiable environmental and healthcare factors. Mass deworming campaigns, improved sanitation, and health education in endemic regions can significantly reduce the risk. Nutritional programmes aimed at alleviating protein and micronutrient deficiencies also play a preventive role. Early identification and management of parasitic infections are vital. Public health surveillance and community outreach are critical components in mitigating the incidence and burden of EMF.

Complications

Uncontrolled or poorly managed endomyocardial fibrosis can result in multiple serious complications:

-

Progressive congestive heart failure

-

Systemic embolisation due to intracardiac thrombi

-

Persistent atrial fibrillation and arrhythmias

-

Severe valvular regurgitation (mitral or tricuspid)

-

Impaired ventricular contractility

-

Sudden cardiac arrest

-

Secondary renal dysfunction due to chronic congestion

These complications underscore the necessity of early recognition and sustained, multidisciplinary management.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with endomyocardial fibrosis is largely determined by the stage at diagnosis and the adequacy of treatment. Early-stage disease, when detected and managed appropriately, may remain stable or even improve. However, in its advanced form, EMF is associated with a high risk of cardiac decompensation, arrhythmic events, and mortality. Surgical interventions, though potentially curative, carry substantial perioperative risks and are not universally available. Prognosis is generally poor in under-resourced settings due to delayed diagnosis and limited access to care.

Epidemiology

Endomyocardial fibrosis shows a striking regional distribution, with the highest prevalence reported in equatorial Africa, parts of India (especially Kerala and Tamil Nadu), Sri Lanka, and northeastern Brazil. In some African cardiology centres, EMF constitutes up to 20% of heart failure admissions. The disease tends to affect younger individuals, with a slight male predominance. Socially, patients often come from impoverished backgrounds with limited healthcare access, which complicates both diagnosis and treatment.

Research & Recent Advances

Recent scientific advancements have enhanced our understanding of the immunopathological mechanisms underlying endomyocardial fibrosis. The role of eosinophils, cytokines, and autoimmunity is being actively explored. Cardiac imaging has also evolved, with MRI and echocardiographic techniques such as speckle-tracking improving diagnostic precision. Genetic studies are investigating susceptibility loci and familial aggregation, potentially paving the way for predictive testing. Ongoing clinical trials in endemic regions aim to evaluate the efficacy of immunosuppressive agents, antifibrotic drugs, and novel surgical techniques. These developments offer promise for more effective disease-modifying strategies.

Case Studies

In a documented case from Kerala, a 14-year-old male presented with chronic breathlessness, hepatomegaly, and oedema. Echocardiography revealed right ventricular apical fibrosis and tricuspid regurgitation. Medical management with diuretics and anticoagulation led to symptom improvement. Another case in Nigeria involved a 25-year-old female who underwent successful endocardectomy and valve repair after presenting with refractory heart failure. These examples highlight the importance of timely, individualised treatment and the potential for clinical recovery.

Summary & Conclusion

Endomyocardial fibrosis represents a chronic, progressive form of restrictive cardiomyopathy prevalent in tropical climates. Although its aetiology remains multifactorial and incompletely understood, evidence supports a central role for eosinophilic inflammation, parasitic infections, and environmental influences. Diagnosis requires a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging, and histological confirmation. Management is complex and must be individualised, often integrating pharmacological, surgical, and complementary approaches. Preventive public health measures are critical in high-risk regions. Continued research is essential to unravel disease mechanisms, improve diagnostic tools, and expand therapeutic options. Raising awareness among healthcare professionals and policymakers is crucial to mitigating the impact of this under-recognised cardiovascular disorder.

References

-

Mocumbi AO. Endomyocardial fibrosis: a form of endemic restrictive cardiomyopathy. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008.

-

Davies JN. Endomyocardial fibrosis in Uganda. East Afr Med J. 1960.

-

Olsen EG. Endomyocardial disease: definitions and classification. Br Heart J. 1981.

-

Marijon E et al. Rheumatic and non-rheumatic valvular heart disease in Africa: a clinical perspective. Lancet. 2012.

-

Lobo RA, et al. MRI findings in endomyocardial fibrosis. Int J Cardiol. 2014.

-

Gnanaraj JP et al. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of endomyocardial fibrosis in South India. Indian Heart J. 2017.

-

Bukhman G et al. Clinical features and management of endomyocardial fibrosis: a review. Global Heart. 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please do not enter any spam link in the comment box